- The Good: Truth and justice are victorious when the brave Tarzan fights

- The Bad: Difficult to read with modern sensibilities

- The Literary: The classic inspiration for a century of spin-offs

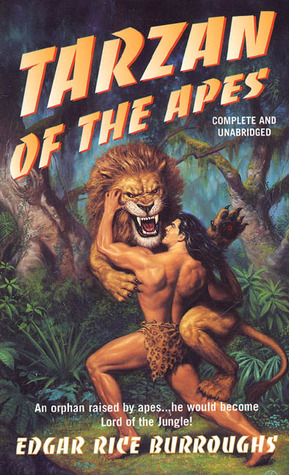

Deep in the African jungle, orphaned infant Tarzan is adopted by a she-ape grieving over her own lost baby. Raised as an ape, Tarzan learns how to survive, hunt, swing through the trees, and speak the language of the animals. He’s embarrassed by his hairless body and his dainty nose until he discovers an abandoned cabin and its books, where he finds pictures of creatures who look like him.

Tarzan of the Apes is the first book in a pulpy adventure series from the early 20th century, but it’s also the source of a myriad of adaptations over the past hundred years. I’m confident you didn’t even need to read my synopsis due to the legendary stature of Tarzan in pop culture. As a species we’ve long been fascinated with the idea of being raised by animals in the wild, and Tarzan delivers. When a man is raised by animals, how much of his behavior is inherent, or the result of nurture? What does it mean to be human?

One the one hand, Tarzan is a pure soul, uncorrupted by civilization, who loves his ape mother and the jungle. He protects his tribe, worries about honor, and falls in love with Jane at first sight. But Burroughs doesn’t shy away from the brutality of the animal kingdom. Tarzan is in touch with his base instincts, killing for food and preferring to eat his meat raw, but he also kills for pleasure. He enjoys competition and violence, drawing a line only at cannibalism.

Speaking of cannibals, early twentieth century racism and sexism is rampant in this book. Tarzan’s youth isn’t without exposure to man. But the black African tribes he encounters are barely human, ignorant, war-hungry cannibals. It isn’t until white men land on the shores that Tarzan recognizes himself in them. And it isn’t until a white woman lands on the shores that Tarzan sees real beauty for the first time. Even Jane’s black maidservant mispronounces words and faints in every crisis. I’m surprised anyone would fall for Jane when she says things like, “Ah, John, I wish that I might be a man with a man’s philosophy, but I am but a woman, seeing with my heart rather than my head, and all that I can see is too horrible, too unthinkable to put into words.”

Tarzan’s success can even be attributed to his lineage as the heir to two upstanding colonial parents. Tarzan’s noble blood allows him to reason and plan for the future, but also to teach himself to read and eventually learn to speak English, French, and German in a matter of weeks. I actually don’t mind this specific stretch of the imagination, but even if Tarzan could decipher the picture of clothing and lamps, understanding words without a key is a nearly insurmountable task.

The sub-title of the novel, A Romance in the Jungle, points to the completely unsubstantial romance between Tarzan and Jane. Upon first seeing Jane, Tarzan recognizes something that must be protected. He stalks her constantly, finally breaking into her room and reading a letter she wrote to a friend while she is sleeping. He leaves the note for her, “I am Tarzan of the Apes. I want you. I am yours. You are mine.” Once Tarzan saves Jane, and Jane sees all those rippling muscles, Jane falls in love as well, forgetting her former flame. Jane recognizes the nobility in Tarzan, a frighteningly powerful and alien creature who cannot communicate, when no one else can, but fails to connect him to Lord Greystoke even though Tarzan wears a locket with his parents’ pictures in it.

I still love the vivid, face-paced adventure scenes in the jungle. Especially Tarzan swinging in the trees. And apparently so do a lot people. It’s iconic and fun, and Burroughs probably did not expect to be judged so harshly when he wrote a pulpy children’s book about a young man who is King of the Apes but wants to know the world from which he came.

“For myself, I always assume that a lion is ferocious, and so I am never caught off my guard.”