- The Good: Complex characters in a sweeping historical epic

- The Bad: Very little fantasy; dense political machinations

- The Literary: Queer cast essential to the narrative

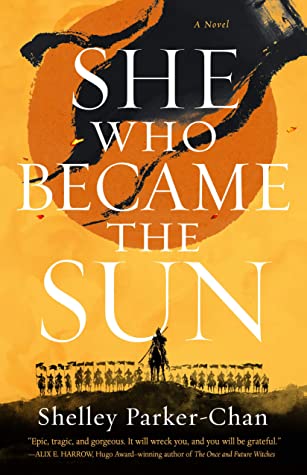

When the Zhu family’s fate is foretold, the eighth-born son, Zhu Chongba, receives a destiny of greatness, whereas his little sister has no such luck. That any of the children will rise above their station seems too good to be true, since the Chongba family is one of the many starving peasants in 1345 China under Mongol rule. Soon after, a bandit attacks and kills the family, only the brother and sister remain—and it’s not long until Zhu Chongba himself dies from despair. The resourceful and capable little sister decides to escape her fate, assumes her brother’s identity, and enters a Buddhist monastery as a young male novice.

You root for the daughter, who eventually assumes Zhu Chongba’s name, from the first page. She captures crickets to eat on the dusty streets and withstands the abuse and degradation from her father. When she kneels in front of the monastery for days without food and water to prove her devotion, it’s just the start of the close calls she faces as she enters puberty, binding her breasts, hiding her monthlies, and avoiding common bath days. Speaking of Zhu’s trans identity, the story refers to she and her, despite every other character perceiving Zhu as a male, and the ongoing confusion of pronouns follows Zhu’s own exploration and evolution.

This historical fantasy re-imagines the rise of the first emperor of the Ming dynasty. Unexpectedly, the fictionalization replaces Zhu with his sister, which gives the protagonist a lot more reasons to fight, as well as a lot more to lose. It’s decidedly inclusive and queer, as much modern scifi and fantasy is, but the modernization is woven expertly into the time, narrative, and character motivation.

The story is grand, a sweeping epic that balances the internal workings of several characters and the politics and religion that force Zhu to play the game to survive. In addition to Zhu, secondary POV character Ouyang is a battlefield general serving the house Temur. He was taken by the Temurs as a child, his life spared though his family was not, castrated and assigned to be a slave to the boy Esen-Temur. Ouyang’s hatred toward Esen and his family is a fantastic revenge tragedy.

The third POV is Ma Xiuying, a woman who is an embodiment of caring, who grounds the story with a likable character who doesn’t lust for revenge. Both Ouyang and Ma serve as catalysts and foils for Zhu, with narrative and character parallels that both invigorate and make the story feel satisfying. Both Zhu and Ouyang fight to escape the stories of their haunted youths, but as antagonists, only one can win.

Although the novel is billed as fantasy, there is little of it. There are some ghosts and the literal manifestation of the Mandate of Heaven. Even though the story doesn’t need these fantasy elements, the fact that it’s promoted as fantasy and a nominee for the Hugo Award, my expectations were set and therefore a little disappointed. I’ve also come to find that dense political maneuvering and war-laden scenes aren’t always my cup of tea, and there’s a lot of that here.

Highly recommended as a dark, brutal, unforgiving tale about anti-heroes who aren’t afraid to sacrifice a means for an end!