- The Good: A dark fantastical take on 1930s Hollywood

- The Bad: Slow pacing; unrealized magical system; overly on-the-nose feminism

- The Literary: Long list of recommended reading and book club prompts for discussion

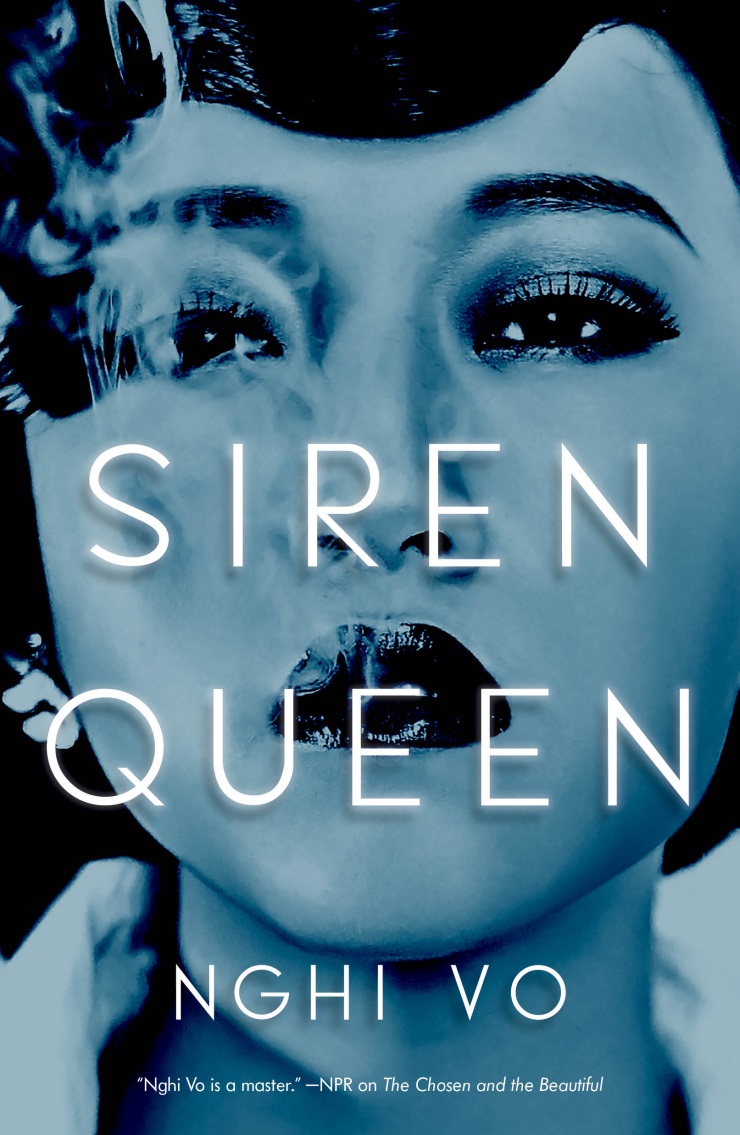

Ever since she saw her first talkie as a little girl, Luli Wei always wanted to be a star. She also knows that there are limited roles for a Chinese American girl from Hungarian Hill. And when she manages—through extortion—to secure an interview with a powerful man in Hollywood, she demands “no maids, no funny talking, no fainting flowers.”

There’s a lot to love about this book. First the pre-code Hollywood of the 1930s is a setting already dripping with myth and nostalgia. But this isn’t a portrayal of a golden age; instead, it’s a critical look at the few powerful men who control the lives of those under contract, including when and to whom they marry, all for the sake of the image of the studio they represent.

My favorite take on the world, particularly the studios, is the magic. Movies are made possible by a series of dark bargains, ritual sacrifice, and ancient magic. If you aren’t careful, the cameras will literally eat the souls of those they film. But immortality is entirely possible, and the most successful actors literally ascend to the heavens to become a star. Luli’s roommate, a beautiful Scandinavian cow-herder was captured and brought to Hollywood against her will, her tail removed so she’d be appropriate for the pictures. Even at home before Luli left for LA, she paid for movies with an inch of her hair and her mother fashioned well behaved dolls, little golems, to replace her and her sister.

I could go on and on with the fantastical details. They pepper the novel like a spice, adding flavor and nuance to a world we only think we know. It’s magical realism at its best. However, the magical elements have no rules and they aren’t there to propel the plot. If you need clear-cut fantasy world-building, you won’t like this.

The story features both Asian-American and queer perspectives through Luli. I particularly enjoy the fact that Luli is boxed in by her face, but when someone speaks to her in Mandarin, she realizes she’s nearly forgotten her native Cantonese, having left her family and their laundry in San Francisco and never looked back. She doesn’t particularly struggle with her identity, but it defines her all the same. On the other hand, her queerness is front and center.

I appreciate that the queer secondary characters aren’t demonized for staying in the closet by choice, or for wanting or not wanting a family. The queer characters aren’t destined for terrible ends. The movie series that propels Luli to stardom is one in which she plays the antagonist, a sea monster, something evil and foreign and unknowable, and it’s a nice thematic representation of her character, her culture, and her sexual preferences.

Highly recommended for fans of magical realism, old Hollywood and the Chop Suey Circuit, and queer fiction!