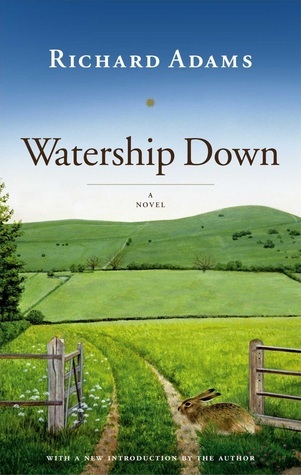

- The Good: Harrowing tale of adventure, courage, and survival… with rabbits

- The Bad: Extremely savage and violent, which is not necessarily bad, but just be prepared

- The Literary: Highly awarded allegorical children’s fiction

Set in England’s Downs, rabbit brothers Hazel and Fiver decide to leave the only warren they have ever known because of Fiver’s horror-filled premonitions. They recruit a small group including Bigwig, Blackberry, and Dandelion, and journey forth to find a new home and build a more perfect society.

Richard Adams claims that there is no intended allegory in Watership Down, that it’s just a story about rabbits he made up to entertain his children on an extended car ride. But even if he didn’t consciously create a story with multiple themes and allegories, he did so unconsciously. Not only is the plot an adventure-filled flight into the wilderness, it’s full of action and quests, predators and adversaries, new friends and alliances, and there’s commentary on leadership, totalitarian governments, community versus individuality, and survival and heroism, just to name a few.

This is a children’s book, but it’s extremely satisfying to read as an adult. It’s quite violent and harrowing, so if you’re thinking Beatrix Potter or Peter Rabbit or The Wind in the Willows, think again. This isn’t a tale of rabbits in waistcoats going on cute adventures. This is a story of rabbits escaping death time and time again, with numerous bloody casualties. Despite the world of brutality and sorrow, the overall tone is optimistic.

There’s certainly also an environmental theme. Humans are an ever-present threat, more similar to natural disasters than other animals. Men kill for no reason, with guns and traps, but also with chemicals and giant mechanical beasts, not for their own survival but with premeditation to destroy as much as possible. (Spoiler: At the end of the novel, a little girl captures the wounded Hazel and saves him from their farm cat, which provides a hope of redemption for humanity after all.)

Two communities of rabbits they encounter live in some form of captivity, and there’s also a theme on what captivity means for wild animals. They become docile and compliant, afraid and untrusting, even deceitful. But as a reader you understand their psychology. Even the antagonist Woundwort is a well-rounded character with a tragic backstory (including some time in captivity) that gives him motivation for his single-minded ethos.

I love the mythology of the rabbits, and the oral tradition of telling stories. El-ahrairah is the original trickster rabbit, and through hearing his tales Hazel and Fiver and the other rabbits learn to be clever and adapt for survival. The Black Rabbit of Inle and his silent warren are terrifying. The invented rabbit language Lapine adds to the rich world of rabbit existence.

Hazel, Fiver, and their band of brothers, manage to balance tradition and innovation, innate and learned “clever” behaviors. They seek to live as rabbits are naturally intended, free and wild, to forage and mate as they please. But in order to do so they dig their own unique burrow, use logs as rafts to cross rivers, and forge alliances across species.

In this review, I tend to refer to the rabbits as a group, but they’re each well-written and detailed, each with their own personalities and individual characteristics. If I had to choose a favorite, it’d be Bigwig, whom I initially didn’t like because he challenged Hazel’s authority and bullied the smaller rabbits. But Bigwig becomes loyal, determined, and willing to sacrifice himself for the warren in multiple ways.

Highly recommended for both children and adults, just be ready for some bloody violence.

“El-ahrairah, your people cannot rule the world, for I will not have it so. All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a Thousand Enemies, and whenever they catch you, they will kill you. But first they must catch you, digger, listener, runner, prince with the swift warning. Be cunning and full of tricks and your people shall never be destroyed.”